The Philippine home has long been presented mostly as an upper-class space in Filipino art. A sweeping look at the interiors of Fabian Dela Rosa’s paintings, for example, would reveal a luxurious salon life replete with towering capiz windows, oriental rugs, and intricate marquetry walls. There would be the wealthy family in the middle of it all, dressed to the nines, ready to entertain guests in a pre-war setting.

As a more recent example of this observation, we could reference Federico Aguilar Alcuaz’s portraits; with his pale-skinned socialites reclining on richly upholstered armchairs or fainting couches with heavy drapes and a hint of a cosmopolitan skyline in the window behind them. Rare are representations of provincial houses, except for the illustrations by Jose Honorato Lozano, which are more of visual chronicles of 19th century life.

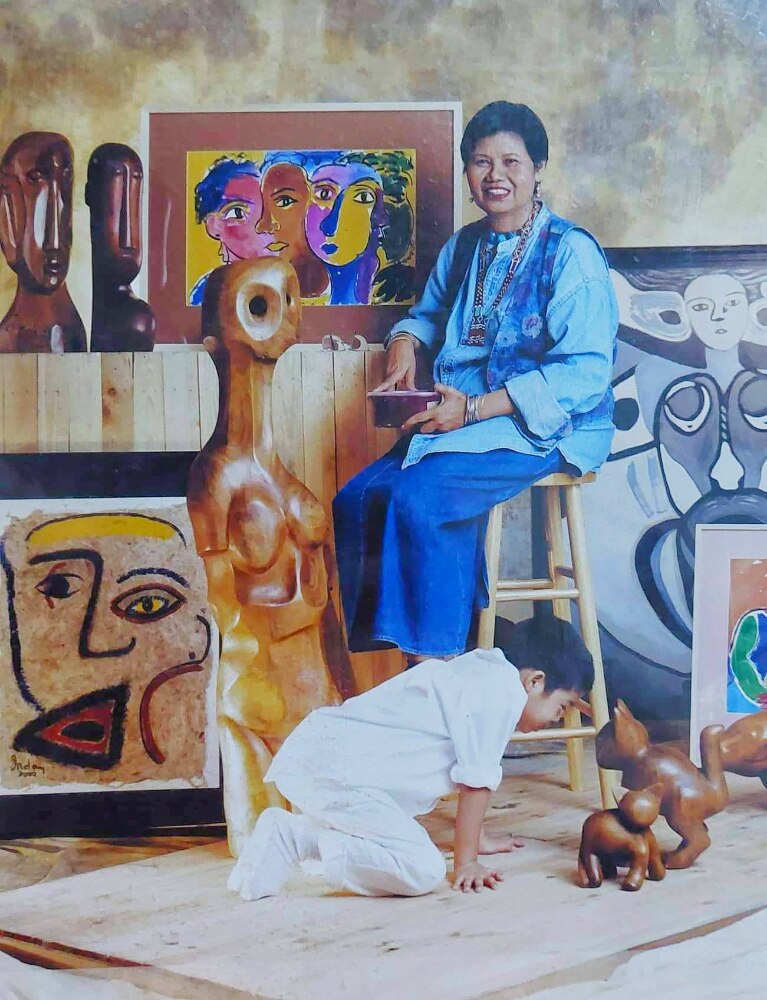

But the late artist Inday Cadapan turned the subject of the traditional Filipino abode upside down by showing middle-class homes in her works wherein simplicity, comfort, familiarity, and warmth are immediately evident.

Middle-class milieu

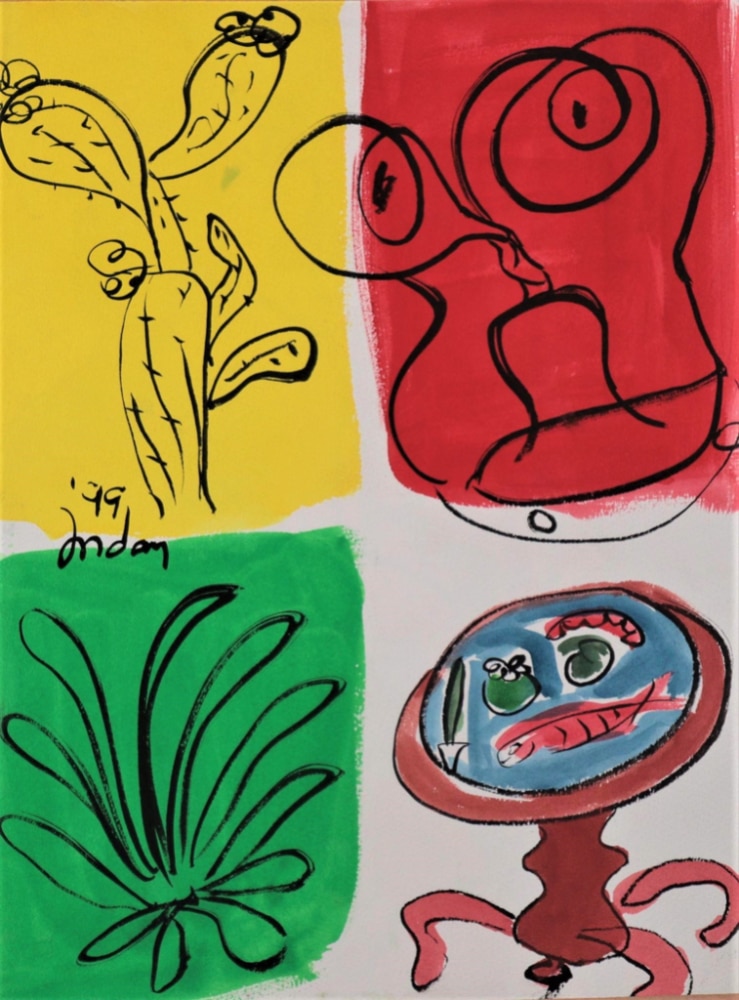

There are no formal spaces or pretense in Inday’s paintings. Small, cozy, and colorful rooms are shown as a woman’s domain. Side tables are topped not with crystal, but with a vase filled with flowers (possibly from the garden!).

The colors of the furniture are mismatched, yet vibrant—red table with blue legs, pink chair with green seat; in these homes, anything goes. And there are no soirees or guests in expensive clothes either; just mother and child, often breastfeeding, sometimes a woman lounging and daydreaming by herself.

Inday’s fondness for interiors could be traced to her background. Magel, Inday’s daughter, shares that the frugal and modest settings in her paintings reflect Inday’s past, when her own widowed but brave mother struggled to raise six children while sewing dresses after the war.

The painting’s interiors also relate to Inday’s former business as an antiques and furniture dealer. She put up her first antiques store at the Mabini Arts Center in the 1970s next to celebrated writer Gilda Cordero-Fernando’s antiques store, and this inspired her to create her own folk furniture pieces with what she had.

Magel recounts the day when a French couple visited their antique store and bought a few of Inday’s paintings. This incident cemented Inday’s drive to create, as she knew the French had a broader appreciation of art and that her own art was finally recognized and accepted.

The Batibot chair

One omnipresent object in Inday’s interior paintings is the Batibot, a small chair made out of twisted wrought iron bars that form the chair’s frame, backrest, and legs, with a circular piece of wood as its seat. Its origins stem from turn-of-the-century Zarzuelas (musical plays) as theater seating; the chairs were nailed to the floor through the loops in its feet.

The Batibot (which literally means “tiny yet strong”) takes its place as the Filipino furniture piece of choice in Inday’s interiors—over the bigger and more formal butacas and tumba-tumba rocking chairs—mainly because of its humble roots.

Before the invention of plastic Monoblock chairs, Batibot chairs were initially used as low-cost yet durable local equivalents of Europe’s Thonet-style bentwood café chairs. The Batibot was a staple chair in the middle-class homes of the 1950s to the early ‘70s, and were used as dining chairs, a study chair, or as an extra seat for surprise guests.

The Batibot was also the seating of choice of many humble restaurants or streetside cafeterias, mainly because of its innate sturdiness, and the ease of how it could be stacked or turned upside down on a table. These chairs are also hard to destroy—even after years of use or from many drunken brawls.

Perhaps it is this stability and resilience that made Inday use the Batibot proudly as the lone seat in her paintings—heavy and holding court, front and center, and without other ornate furniture pieces in sight. The artist seemingly used the Batibot as the “great equalizer,” the sole seat for all members of the family and for people of all classes, just because it was there and it was available.

Of course, it is only Inday who would have noticed that the intertwining loops of the chair’s backrest looked like kissing lovers, a mother’s breasts, or a woman’s womb; or that the twisted metal of its legs seemed like human feet. In these paintings where the chairs come to life, it is the Batibot that symbolizes femininity, or is representative of woman herself, “tiny yet strong.”

The house of Inday

One cannot talk about Inday Cadapan’s paintings about the home without mentioning her own home. The late artist’s Antipolo house has since been transformed into a home gallery and in a previous iteration, a café and shop. Stepping into it is like entering Inday’s world.

The house’s yellow walls and turquoise Ambassador chairs are real-life manifestations of Inday’s paintings. There are bits and pieces of traditional bahay-na-bato details attached to the house: callado transoms, Capiz windows, and gallinera benches that would have felt at home in her antique stores. Magel relates that her mother constantly recycled old architectural details and furnishings, and utilized the massive amounts of scrap wood that she had; it was her dream to renovate her house and turn it into yet another art form.

An imposing seven-foot-tall “People Power” wood installation by the artist, which used to sit outside the GSIS building, now lords over the living and dining rooms. There are weathered pieces all throughout that have been given the Inday touch—a broken dama juana glass jar among them. Instead of throwing it away, Inday painted a mouth over the broken part and eyes above it. The jar’s hole is now frozen into a permanent scream.

Inday’s home is a maximalist’s dream, yet even those who love minimalist spaces would possibly find comfort in its warm and happily-colored rooms. The spaces do not apologize for its exuberance, much in the same way that the artist never apologized for her art. And even though Inday had passed on almost 20 years ago, the home is infused with her essence; a work of art itself where all are welcome.

A retrospective of Cadapan’s works is showcased in “The Many Faces of Inday Cadapan” which will run until November 12 at Fundacion Sansó, 32 V. Cruz St., San Juan. See it Monday to Saturday, 10am-4pm (except holidays). For more information, visit @fundacion_sanso on Instagram and FUNDACIONSANS0 on Facebook or email [email protected].