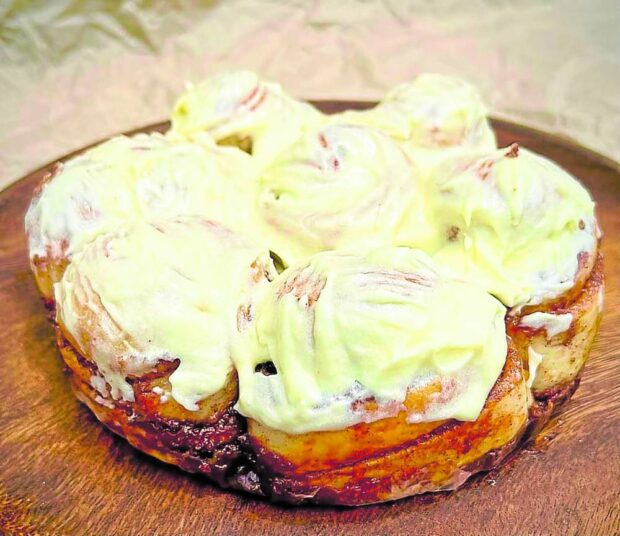

One of their “ensaymada” products. (Photo from BOY PANADERO)

LOS BAÑOS, Laguna, Philippines — The man behind a neighborhood bakery in Calamba City in this province pines for the long-lost flavors of the Filipino “panaderia” of old, while harboring dreams of success beyond the local market.

Norman Rey Ramos believes he and his staff have what it takes, thanks to the training he had received in Australia, and — perhaps more crucially — to the support extended by the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) during a pivotal period for his business.

With a degree in food technology earned at Le Cordon Bleu in Sydney, the pastry chef and chocolatier recalled being “impressed by the methods and techniques” he learned there.

Ramos now hopes to replicate such “bread culture” back home, for the local panaderia of today “seemed to be deteriorating,” he said in an Inquirer interview on Sept. 18. “Filipino bread doesn’t taste the same as before, in part because of commercialized methods.”

When he returned to the country from Australia in 2010, Ramos broke the hardened mold, so to speak, by using sourdough starters on mass-produced bread. Though slower and more complex than using commercial yeast, this artisanal approach produces sourdough bread that is more nutritious and has a longer shelf life, he explained.

“After all, bread is essentially the process of fermentation,” he said. “The longer it ferments, the more the bread is allowed to develop its flavor.”

This “secret recipe,” as he called it, is the driving force behind Boy Panadero, the bakery he had built in the hope of recapturing a lost era in Philippine bread culture—when neighborhood pastry shops produced ample-sized and truly tasty “pan de sal,” “monay” and banana bread, among others.

Starting out in 2013, Boy Panadero has since expanded into a commercial producer of pan de sal, rolls, sweet breads, “ensaymada,” and sliced bread.

It was one of the businesses supported by the Small Enterprise Technology Upgrading Program (Setup) of the DOST, which offers seed money and technical assistance to micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

Science and Technology Undersecretary Sancho Mabborang said several enterprises in the Calabarzon region (Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, and Quezon) being supported by Setup are, like Boy Panadero, involved in food or food processing.

Emelita Bagsit, the DOST director for Calabarzon, said Ramos’ business was an example of how local panaderias that start small could modernize and become more competitive.

Ramos noted that while the local bread industry had indeed become competitive, with panaderias opening on every other street corner, the products being churned out tended to be inconsistent in quality.

“I noticed that some bakeries don’t know how to make bread properly,” he said.

ENRICHING ‘BREAD CULTURE’ | Norman Rey Ramos (left) and his Boy Panadero staff, here being supervised by his father Manny (right), were among the first to receive support from the Small Enterprise Technology Upgrading Program of the Department of Science and Technology. (Photo from BOY PANADERO)

Sourdough technique

The typical pan de sal, for example, is made of wheat flour, sugar, salt, and water but some bakeries “would make it like a cake mix; they would add condensed milk or vanilla flavor.”

“The old traditions are vanishing,” he said.

Ramos learned about Setup in 2022 after his father Manny saw a DOST ad in the Inquirer that called for applicants to the program.

He was then running his bakery in Barangay Milagrosa—but it was limited to online transactions because of the pandemic.

“But there was a demand for bread then, in Laguna and Manila … and we wanted to scale up our operations,” he said.

Thanks to Setup, the bakery was able to upgrade: it was given a rotary rack oven that could bake 900 pieces of pan de sal per hour, as well as a bread-forming machine and loaf bagger to further streamline the process.

The bakery follows a relatively simple procedure: the workers use factory-grade mixers to create the bread mixture, which is then “proofed” (with the yeast activated) in the bread-forming machine. A second proofing is done before it is baked and the final product is sent for packaging.

Ramos believes his bakery was one of the few using this method on a commercial scale. It’s not common because “you first need to understand the science behind it,” he said.

The Setup program helped his bakery perfect its sourdough technique while raising the efficiency of its operations.

‘Comeback’

Boy Panadero will soon produce the latest DOST version of the “nutribun,” he said, referring to the bread produced during the first Marcos administration in the 1970s and handed out to school children.

The nutribun program is currently being redeveloped by the Food and Nutrition Research Institute.

While Boy Panadero’s bread is sold mainly in Laguna province, Ramos said the business is awaiting clearance from the Food and Drug Administration to distribute its products in supermarkets nationwide.

He now hopes to witness the revival of the bread quality he enjoyed as a child — soft, sweet-smelling, and just perfect for breakfast.

“I want to see our local bread regaining that old prestige,” Ramos said. “It’s part of our heritage and identity.”